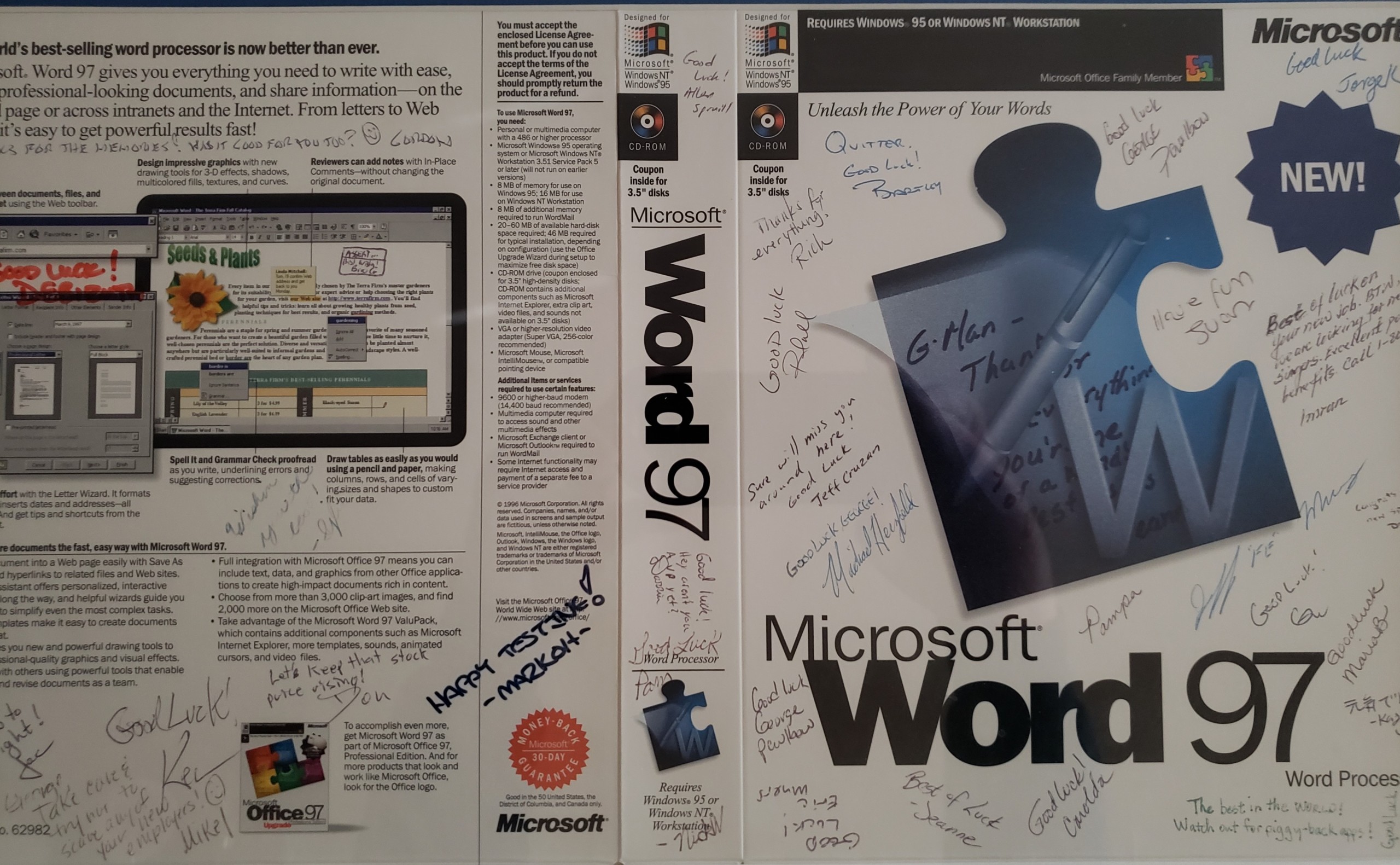

In chapter 18 of my book Get Back Up Suzie and I have left San Jose for Redmond, Washington, where I would be starting a new role as a test lead on Word, Microsoft’s word processing product. I had done all I could in the PowerPoint group to move up in the organization, but since they only worked on this one product and only had the need for one test manager, my next move was limited. Redmond was Microsoft headquarters so there were many products and many opportunities to continue my path forward.

My move to Word was a lateral one, meaning that I was a test lead on PowerPoint and so I would be a test lead in Word. The difference was that PowerPoint had a test team made up of 16 testers, four leads, and one test manager. Word had 60 testers reporting to eight leads who all reported to a single test manager. That test manager was Jeanne Sheldon. Jeanne knew my next goal was to become a test manager and she was willing to work with me toward that end. She was not only my boss but a mentor, and she really knew a lot about testing and managing people. She continued to teach me a lot as I grew in my role as a lead.

My first assignment was to manage the testers on the workgroup feature set of Word. I was also given a small but important side project working on a way to access information on the internet. Thus, I started out with two teams. As I’ve said before, to get the job you want, perform your current job well and start doing the job you want in addition. The two main differences between a test lead and a test manager are: 1. The test lead manages the individual contributors testing the product while a test manager manages the test leads. It is the first manager of managers level. 2. The test manager, in partnership with the group program manager and the development manager, work together to manage the business.

While I could certainly give feedback to Jeanne about running the business, it wasn’t really a job I could start doing before I had it. I could, however, start managing managers but the first thing I had to do was own enough of the business to justify an additional level of management.

I already had two teams and now another opportunity was about to come my way. The PowerPoint group at that time wasn’t big enough to justify an automation team so that presented an opportunity for me to work in that area, and with Chris and Anil we were able to take advantage of that opportunity by creating the automation tool Test Case Generator (or TCG) that I mentioned in my last blog, and in chapter 17 of my book.

Word had an automation lead with five people working for him on tools and automation, and this lead had just announced that he was leaving the team. Because I had worked on automation Jeanne came to me and asked if I knew anyone who could take over that team. I told her yes, me. She then asked if I knew someone who could take over my existing teams, and again I said yes, me. She pointed out that this would be a lot of work but I said I wasn’t worried about it as each of my teams had a senior person who, while they wouldn’t technically be a lead—that is, the people wouldn’t be reporting to them and they wouldn’t write their reviews—they could be a technical lead and manage the work and the direction of the team.

Jeanne said that could work and agreed to allow me to give it a try. I now had three teams with technical leads over each. I was kind of a manager of managers. I was on my way to doing the job I wanted when yet another opportunity came my way.

There was another group in Microsoft working on a company-wide test tool that they no longer had the resources to work on and so they planned to cancel it. Jeanne heard about it and asked me if I wanted to take on this work as well. Of course, I said yes. Jeanne wasn’t surprised but she did point out that I already had a lot on my plate. She went on to say that she would continue to pile things on my plate until I said I had enough. I told her to keep piling because I wasn’t about to say no. It wasn’t as if I was doing all this work myself. I had some great people working for me, and I had great leaders who could help me keep things moving forward. This team wouldn’t be any different.

Around this time, I was also getting a reputation for building great teams and weeding out people who were underperforming. Jeanne noticed this and began to move these folks to my team. You would think that people would start to be afraid of being moved to my team for fear of being managed out, but it turned out to be exactly the opposite. I’ve always said that any idiot manager can fire someone, but it takes a good manager to turn a person around.

Any time I was given one of these challenge employees, I would sit down with them and try to find out what the issue was. Sometimes it was just that they didn’t have the skills they needed. If that was the case, I would make sure they got whatever training they lacked. Sometimes they were just in the wrong job altogether. In that instance, and if I thought they would be successful in a different role, I would help them find it.

I would never transfer a problem to another team. If I wasn’t sure that an employee would be successful, they would stay with me. I found that people who aren’t doing well usually aren’t happy in general. They’re also often under a lot of stress in their current situation. But even though they’re unhappy, they don’t want to lose their jobs: a lot of people fear change, and it’s better to have a job you hate than no job, right?

Another thing I noticed from underperformers is that they often didn’t get the feedback they needed in order to adjust. Sure, Microsoft had its review process, but that was a formal way to get feedback on your goals and objectives twice a year so that you could be rewarded for your successes. Of course, that only happened if you actually had successes.

For some of these people, the twice-yearly performance reviews were the only times they were getting feedback. Sure, it is easy for managers to say, “good job,” but few people like confrontation, so they save the comments that essentially say “bad job” for the review. The problem with this, however, is that by then it’s too late. No one wants to hear how they could have done better at a task months after the fact, when the rewards are being given. They need to hear this along the way, when there’s still time to do something about it.

I decided that on my team, we would do things differently. Every week, I would meet with my direct reports in one-on-one meetings. This meeting was mostly to talk about the issues of the day. Additionally, at the first one-on-one of the month, we would sit down and discuss the employee’s goals and objectives, as well as how they were doing. This way, they had time to adjust their course before the actual review. This turned out to be a very successful practice, and other teams started to implement it as well.

My time in Word went by quickly. About eighteen months after I’d arrived, we shipped the first and only version of Word that I worked on. Close to the release date, the product unit manager of Publisher realized that she needed a new test manager, and asked Jeanne if she knew of anyone who could do the job. I’ll always remember Jeanne’s reply. She said, “Yes, I know someone. In fact, he’s kind of a baby test manager already.”

I was in Word for less than two years and only worked on one release before I was on my way to becoming the test manager of Microsoft Publisher. This was another case where I did exactly what it took to move ahead at Microsoft: I started to demonstrate the ability to fill a role before I actually had it. It worked before, and it had worked again.

Lessons:

- Instead of waiting for opportunity to knock on your door find another door.

- Make sure you find a great mentor who can help you achieve your goals.

- Do the job you want in addition to the job you have, not at the expense of it.

- Never pass up an opportunity to expand your scope of influence and impact.

- Surround yourself with great people and give them the feedback they need to be successful.

- Any idiot manager can fire someone, but it takes a good manager to turn around a struggling employee.

George A. Santino helps people who want to break down barriers, including self-imposed barriers, to success. Check out his Amazon bestselling book, Get Back Up: From the Streets to Microsoft Suites.